The energy transition is fundamentally changing how the electricity system operates. In many countries — including Switzerland — the expansion of variable renewable energy sources such as photovoltaics (PV) and wind, as well as the electrification of heat, mobility, and industry, is leading to more volatile electricity supply and more complex consumption patterns. This introduces new challenges to conventional control scheme in power systems for maintaining system balance and rises the need for more flexibility to prevent grid instability. Flexibility is therefore a central mechanism to make the energy transition technically feasible and economically viable.

The need of flexibility at different levels and timescales

Flexibility in the energy system refers to the ability of energy assets, such as power plants, grid infrastructure, or consumer devices, to adjust their electricity production or consumption over time in response to changing system needs. Flexibility is required at multiple levels, each with its own specific requirements, challenges, and opportunities.

- System level: This concerns the overall balance of generation and consumption across larger regions, such as the entire country. As the share of renewable energy sources increases, so does the need for flexibility , such as frequency regulation, and seasonal balancing mechanisms, to reliably compensate for short-term peaks and longer periods of low generation [1].

- Distribution grid level: Local bottlenecks and voltage fluctuations may arise due to strong power injections to the distribution grid (e.g., PV in residential areas) as well as strong power consumption such as peaks from electric mobility. Flexibility in the form of targeted load shifting and intelligent control of injections can help reduce grid congestion and make grid expansion more efficient [2].

- Asset or consumer level: Households, commercial buildings, or industrial facilities have controllable devices such as heat pumps, battery storage, or EV charging infrastructure. These can be actively managed for purposes such as self-consumption optimization, peak shaving, or even participation in flexibility markets.

Source: BKW

The need for flexibility varies not only geographically but also over time. Flexibility can be classified into different timescales:

- Very short-term flexibility (seconds to minutes): Required for frequency regulation and primary/secondary control, ensuring that electricity production and consumption remain balanced in real time.

- Medium-term flexibility (hours to days): Enables smoothing of peak loads or targeted use of generation peaks — such as midday PV output — by shifting charging for EVs or heat pumps.

- Long-term flexibility (weeks to seasonal): Addresses seasonal imbalances between winter and summer. Solutions range from thermal storage and power-to-heat to seasonal energy imports and exports [3].

The transformation of the energy system is accompanied by growing flexibility needs at all levels. While the system level was the primary focus, distribution system operators and individual consumers are now increasingly in the spotlight. They are examining how they themselves can utilise flexibility. The variety of actors involved and the different temporal requirements demonstrate that flexibility is not a single instrument but a system of multiple building blocks.

Opportunities and Limits of Flexibility

Flexibility thus means being able to specifically balance fluctuations in the energy system. Controllable assets adjust their operation flexibly and respond to over- or under-supply in the electricity system to maintain balance. Flexibility enables the integration of renewable energy as well as the electrification of the transport and heating sectors.

A critical question is how this flexibility should be harnessed most sustainably. While new storage solutions such as battery systems or hydrogen technologies receive much attention, a significant, largely untapped potential exists in existing infrastructure. Existing devices and systems — from heat pumps to industrial processes to charging infrastructure — can be used flexibly without requiring additional resources or costly new construction on a large scale. Studies show that this so-called demand-side flexibility (DSF) can reduce total system costs, facilitate the integration of renewable energies, and relieve the grid [4, 5, 6].

However, the broad adoption of DSF faces challenges: Many assets are not yet technically prepared or have incompatible interfaces. To address this, industry-wide standards and interoperable technologies are needed to enable decentralized flexibility. Regulatory frameworks often hinder market access for smaller consumers. Finally, behavioural factors are important: Consumers must be willing to provide flexibility, which raises questions of comfort, data protection, and acceptance.

Source: BKW

The increasing digitalization of the energy system also fundamentally changes flexibility requirements. Smart meters, IoT devices, and automated energy management systems make it technically possible to use flexibility efficiently even in decentralized, small-scale units. At the same time, new challenges arise from rising electricity demand from digital technologies, especially in data centres and AI applications. Forecasts suggest that global electricity demand from data centres could more than double by 2030 [7]. This adds additional, potentially volatile demand, and further increases the need for flexibility. At the same time, artificial intelligence offers solutions: By providing more accurate forecasts of generation and demand and through more advanced optimization and control methods, AI can help harness and utilize flexibility more efficiently.

Conclusion and Outlook

Flexibility is a pillar of the energy transition, an era characterized by intermittent renewable sources and sector coupling. It is crucial to leverage the full spectrum of available options, from large-scale power plants and storage solutions to distributed small-scale flexibility. The latter offers the opportunity to use existing infrastructure sustainably but requires technical adjustments, regulatory innovation, and societal acceptance. Digitalization and artificial intelligence can act as enablers by making complex systems manageable and enabling new business models. It will be essential that all actors — from grid operators to companies to private households — are integrated into this new, flexible energy system.

References

[1] Swissgrid (2024): Annual Report 2024.

[2] BKW (2023): Impact of the energy transition on Swiss distribution grids.

[3] ETH Energy Blog (2021): The role of seasonal storage in decarbonizing the energy system.

[4] ENTSO-E (2021): Demand Side Flexibility in Europe.

[5] Eurelectric (2022): Flexibility and the role of DSF.

[6] Fraunhofer ISE (2023): Demand Side Management in der Praxis.

[7] International Energy Agency (2023): Data Centres and Data Transmission Networks.

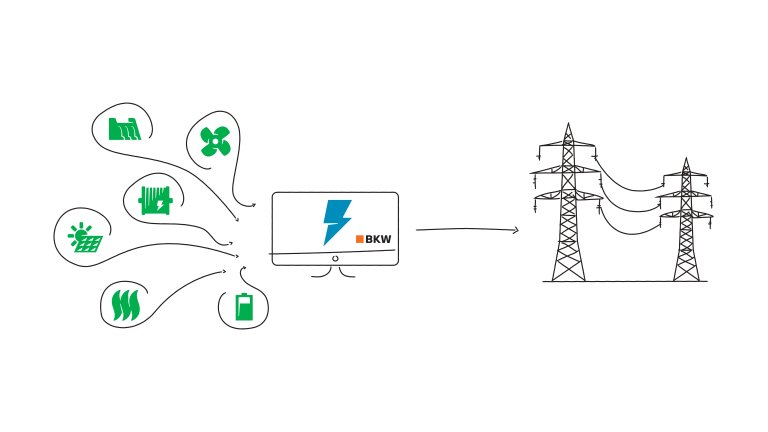

BKW Powerflex

With Powerflex, BKW offers a solution to make decentralized, small-scale assets active participants in the energy system. Through secure and scalable connections, controllable assets such as PV systems, industrial loads, or heat pumps are aggregated into a virtual power plant. Many small assets can thus act collectively like a large power plant and use their flexibility strategically in the energy system. Intelligent control allows the flexibility of these assets to be used, for example, to maintain system balance: in the event of short-term electricity shortages in the grid, individual heat pumps can be automatically switched off for a short period, contributing to overall system stability. Solutions like Powerflex demonstrate how technical innovation and collaboration among all actors can make the energy transition possible.